In exploring optimal solutions for Cake Wallet to offer user-friendly, non-custodial Lightning capabilities to users, the author has conducted an in-depth examination of both Spark and Ark. These innovative approaches to Bitcoin Layer Two networks are fundamentally designed to enhance interoperability with the broader Bitcoin network for payments through the Lightning Network. While primarily utilized for Lightning payments, both networks are poised for extensive functionality that extends beyond this primary application in the coming months and years.

It is noteworthy that, despite initial similarities, the practical implementation of Spark and Ark reveals distinct characteristics.

The Need for New Layer Twos

Fundamentally, Bitcoin serves as an exceptionally empowering tool; however, due to constraints in block size, it is evident that the majority of potential users may never transact directly on-chain. This is where the Lightning Network presents a solution, facilitating an environment where a single on-chain transaction can endorse virtually limitless off-chain transactions, thereby amplifying Bitcoin’s base layer usability and allowing broader access for users.

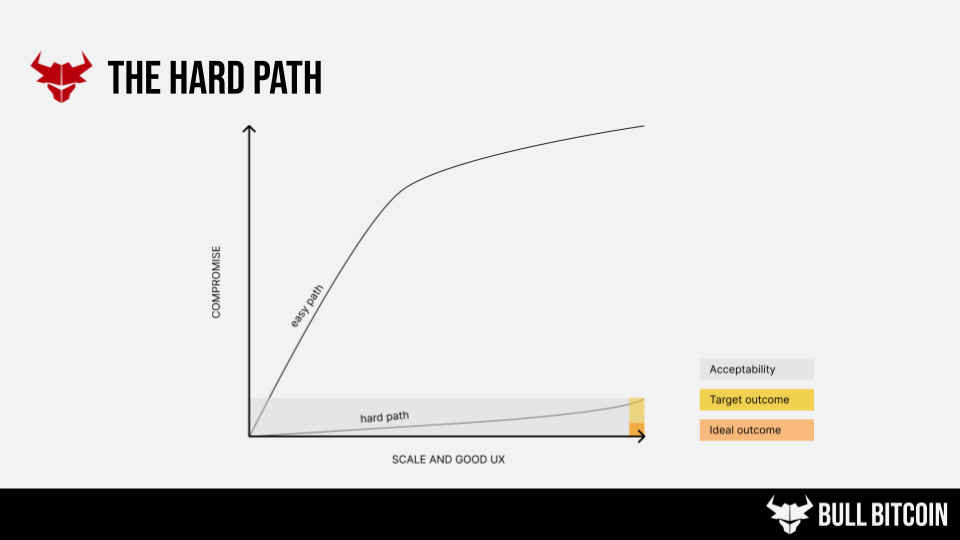

While Lightning offers promising potential for scaling Bitcoin payments, it has become increasingly clear that its optimal function lies as an interoperability layer rather than as a self-managed solution for end-users. On-chain prerequisites, liquidity management, and additional core challenges complicate the deployment of user-friendly, self-custodial Lightning solutions. As a result, most Lightning wallets and usage cases have resorted to custodial or federated models to simplify user experience and implementation.

The primary advantage offered by Spark and Ark within the Bitcoin ecosystem is the provision of a significantly simplified mechanism for developers to integrate Lightning for their end-users, while also paving the way for expanded functionalities that extend beyond mere Lightning payments.

Understanding Ark

Background

Ark was conceived in May 2023 by Burak, a proponent of Lightning technology and an experienced developer. The motivation behind Ark’s development stemmed from the realization that the existing architecture of the Lightning network was ineffective as an onboarding tool for the average user, primarily due to inbound liquidity constraints and other challenges. Although Burak initiated the protocol, it has since been further developed into a complete Layer Two network for Bitcoin by two entities—Ark Labs and Second.

While both organizations work with the same open-source Ark protocol, their implementations and objectives diverge significantly. Therefore, a detailed distinction between the two will be provided where possible.

Key Terminology

Ark: This is a protocol facilitating the movement of Bitcoin transactions off-chain, employing multisig and pre-signed transactions between users and the Ark Operator. It allows for all functionalities of Bitcoin, but with enhanced speed and reduced fees.

Ark Operator: The organization managing the centralized Ark server infrastructure, responsible for liquidity provisioning for users’ VTXOs prior to expiry.

Lightning Gateway: This entity enables Ark users to send or receive Lightning payments via trustless atomic swaps of Ark VTXOs. This role can be fulfilled by the same entity as the Ark Operator, though it is frequently established separately to distribute counter-party risk.

Virtual Transaction Outputs (VTXOs): Similar to on-chain UTXOs in function, VTXOs exist off-chain and are exchanged among users within Ark.

Rounds: To achieve true finality and refresh VTXOs, Ark users are required to engage in rounds, collaborating with other users and the Ark Operator to obtain new VTXOs, typically in exchange for a fee.

Transaction Mechanics

Ark operates similarly to on-chain Bitcoin transactions, inheriting many characteristics while facilitating near-instantaneous and trust-minimized transactions among participants. The sender collaborates with the Ark Operator to transfer the VTXO to the recipient or, in the case of Ark Labs, to create a new, chained VTXO for the recipient. This enables a user experience akin to on-chain payments while significantly lowering fees and expediting transaction times. For Lightning payments, users can collaborate with a Lightning Gateway to atomically swap VTXOs as required. Offline receipt for Lightning payments within Ark is currently unfeasible, although solutions are anticipated to emerge that maintain a trust-minimized model similar to that of Spark.

Should users seek payment finality—such as for substantial transactions—they can opt to participate in a round to finalize the payment, thereby acquiring comparable finality assurances to those offered by on-chain Bitcoin. The frequency of these rounds is dictated by the Ark Operator, with estimates ranging from every 10 minutes to hourly, necessitating a coordinated signing process among all users involved. Round frequencies may also vary based on demand, allowing flexibility unlike the fixed structure of Bitcoin block times.

Given that Ark inherits Bitcoin’s scripting and UTXO model, it is anticipated that Ark will eventually support token protocols such as Taproot Assets.

Trust Considerations

Ark adopts a trust-minimized approach to scaling Bitcoin, achieving a middle ground in usability and trade-offs between Lightning and Spark. It is essential to note that Ark is rapidly evolving; thus, some of the existing trade-offs may be addressed through novel off-chain methodologies or future covenant implementations within Bitcoin.

Finality Concerns

Although Spark does not provide provable finality, Ark represents an intermediate solution. For smaller payments, users can depend on the Ark Operator and prior senders not to collude, facilitating instant transfers without collaborative signing rounds. However, default payments within Ark will be “out-of-round,” lacking true finality, a trade-off made to deliver a positive user experience immediately.

Conversely, users requiring true finality can join a round to receive a new VTXO from the Ark Operator, thereby gaining control over their preferred trust model.

VTXO Expiration

To maintain liquidity for the operation of Ark instances, Ark Operators necessitate a systematic approach to reclaim liquidity. Consequently, Ark VTXOs have predetermined expiration periods (e.g., typically 30 days, with specifics determined by each Ark Operator), necessitating user action to join a round to refresh their VTXOs or risk forfeiting control over their funds. Although Ark Operators possess a substantial incentive to issue new VTXOs promptly to users when they return online, both parties retain the capability to utilize the funds until a new VTXO is officially issued.

To circumvent expiration, users must refresh their VTXOs within the specified timeline, either directly or by delegating the task. An alternative mechanism, such as atomic swaps for expiring VTXOs, could be arranged but remains in the conceptual stage for now.

User Experience Complexity in Rounds

Users familiar with Coinjoin will recognize the challenges associated with collaborative transaction signing. In Ark, users aiming for true VTXO finality must be present for the signing process throughout a round, relying heavily on other participants’ timely contributions. While straightforward for a wallet operating on a consistent server, this requirement proves considerably intricate on mobile platforms, particularly iOS, where background execution is not guaranteed for any application.

To alleviate this complexity, Ark Labs has introduced a mechanism whereby delegated third parties can perform refreshes in a trust-minimized manner, thus offloading the onus of participation from the user. Should delegates experience downtime or decline to refresh an expiring VTXO, users may be compelled to join a round before the designated period concludes. However, users can mitigate this risk by designating multiple delegates, shifting their trust model to a 1-of-N scenario, wherein any honest delegate ensures proper refreshing of their VTXO.

Second has similarly designed a system facilitating trustless, non-interactive rounds that allow multiple parties to sign on behalf of a user during a round. Thus, if any participating party effectively signs, the user’s VTXO will be correctly refreshed.

While these solutions can refresh expiring VTXOs, true finality can only be achieved with user participation in the signing process.

It is noteworthy that numerous complexities inherent to round processes may be entirely resolved with the deployment of a simple covenant in a future Bitcoin update, resulting in a significantly enhanced user experience for Ark.

Privacy Considerations

At its fundamental level, Ark retains Bitcoin’s inherent privacy shortcomings and does not offer notable advancements in privacy as a protocol. Nevertheless, its capacity to execute actions off-chain and broaden Bitcoin’s functionality may facilitate the development of existing and new privacy protocols in the future, particularly with covenants potentially enabling private rounds within Ark.

In the interim, Ark Labs aims to implement WabiSabi-like blinded credentials to enhance user privacy from the operator during participation in rounds.

Transaction Visibility

While transactions within Ark are not mandated to be published on-chain, which affords a degree of ephemeral privacy, all transaction details remain accessible to the Ark Operator and should not be perceived as entirely private. Thus, conceiving Ark’s temporary privacy as analogous to a VPN model—where transaction visibility is transferred from the Bitcoin blockchain to a trusted third party—serves as a beneficial conceptual framework.

Future intentions by Ark Labs and Second to either maintain transaction data confidentiality or publicly disclose it remain uncertain. Users should refrain from relying solely on assurances of non-logging for their privacy, similar to a VPN model.

Further Reading

- Official documentation (Ark Labs): https://docs.arkadeos.com/

- Official documentation (Second): https://docs.second.tech/

- Insightful video explainer on Ark by Second: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WvwmLv0SgAc

- “Ark and the Train Analogy” article: https://pakovm.substack.com/p/ark-and-the-train-analogy-a-guide

Understanding Spark

Background

The Spark network was inaugurated earlier this year by Lightspark, a Bitcoin-adjacent enterprise with a unique history. Their previous endeavors, ranging from UMA (a username system with compliance features integrated for their banking partners) to involvement with the discontinued Libra currency, reflect a somewhat atypical trajectory in building tools not traditionally aligned with Bitcoin’s cypherpunk ethos. Nevertheless, upon evaluating the Spark protocol on its own merits, it emerges as a pragmatic and robust tool in various contexts.

Spark fundamentally incorporates the advantageous elements of statechains, a novel Layer Two concept introduced by Ruben Somsen in 2018. Notably, Spark extends statechains through the implementation of “leaves,” enabling users to transfer any amount in a transaction, rather than being restricted to whole UTXOs—a significant challenge encountered with statechains thus far.

Key Terminology

Spark Entity: This refers to the organization managing a specific Spark instance, exemplified by Lightspark, which consists of multiple Spark Operators. Given that Spark is an open-source protocol, any individual or organization can establish their own Spark Entity; however, each entity retains control over which Spark Operators are permitted to join.

Spark Operator: Each Spark Entity comprises one or more Spark Operators responsible for validating and endorsing user operations within the Spark instance, such as fund transfers and token issuance. This role can be fulfilled by the same entity as the Spark Entity, or ideally, maintained independently to ensure distinct relationship and jurisdictional separation. Currently, the two Operators for Spark are Lightspark and Flashnet, with additional operators anticipated in the future.

Spark Service Provider: An entity providing various services to Spark users, including atomic swaps for trustless sending and receiving of Lightning payments on behalf of users.

Spark Leaves: Spark addresses the problems associated with whole-coin transfer requirements in statechains through the introduction of leaves, akin to UTXOs in Bitcoin, which can be fragmented into any necessary size.

Transaction Mechanics

At its essence, Spark facilitates the near-instantaneous movement of Bitcoin within the Spark network through a trust-minimized collaboration with Spark Operators, allowing users to transfer ownership of individual leaves effortlessly. Transactions do not rely on blockchain confirmations or liveness between sender and receiver, making payments swift and straightforward. For Lightning payments, users can engage in atomic swaps of leaves with Spark Service Providers, who then execute the payment on users’ behalf for a fee.

To enact the transfer of a Spark leaf, the sender co-signs ownership with Spark Operators to transition the leaf to the new owner. This method ensures that if any of the Spark Operators or previous owner delete their keyshare utilized in the co-signing process, the leaf is irrevocably transferred to the recipient, while mitigating the risk of double-spending. The collaboration required for these signing rounds negates the need for involvement from other Spark users, rendering these processes extraordinarily rapid and resistant to denial-of-service attacks.

In addition, Spark implements a similar 1-of-N trust model for offline receipt of Lightning payments, representing a substantial enhancement in user experience when contrasted with conventional Lightning wallets. This is particularly salient for mobile wallet applications, as mobile platforms do not guarantee persistent background execution or uninterrupted network access.

Moreover, Spark has extended its capabilities to include native token support, focusing primarily on stablecoins such as USDT and USDC, enabling seamless issuance and transfer within the Spark network. Token transfers maintain the same trust model as regular transactions on Spark and allow for unilateral on-chain exits when necessary.

Importantly, users in Spark retain the ability to exit unilaterally to the on-chain environment at any time by deploying a pre-signed exit transaction. The costs associated with exiting may fluctuate due to factors such as leaf depth and on-chain fee rates, which may prohibit smaller amounts; nevertheless, it serves as a critical mechanism for ensuring fund retrieval in the event of a non-compliant or unavailable Spark Entity.

Trust Considerations

Spark offers a pragmatic series of trade-offs in response to the ongoing challenges facing both Lightning and Bitcoin usability today. The term “trust-minimized” is preferred when discussing Spark, as only self-custody of on-chain Bitcoin can be regarded as genuinely “trustless.”

Lack of True Finality

The principal risk to self-sovereignty within Spark stems from the absence of definitive finality, as users cannot ascertain with certainty that their funds are immune from potential double-spending resulting from collusion between Spark Operators and a previous spender. Finality exists within Spark—indicative of knowing that funds can only be transacted with designated private keys—yet this is not provable unless a single Spark Operator deletes their keyshare post-transaction. Conversely, if all Spark Operators engage in malicious conduct, they may be capable of double-spending a leaf and thus expropriating funds.

While the 1-of-N trust assumption appears reasonable in practice, it significantly diverges from the default trust assumptions inherent to on-chain Bitcoin, where true finality is guaranteed. Moreover, given the pseudonymous nature of Spark transactions, the previous sender could potentially be the same entity as the Spark Entity itself.

Centralized Token Control Risks

Although token transfers follow the 1-of-N trust framework similar to standard Spark transactions, tokens can be frozen at any moment if the issuer opts to enable such functionality. This is akin to frequently centralized stablecoins like USDT, which have been subject to freezing and confiscation for regulatory purposes, and is an important consideration for regulated stablecoins such as USDC and USDT.

1-of-N Offline Lightning Receive Security

While offline Lightning receives do not possess the same trust-minimized assurance as standard Lightning transactions, the theft of funds via collusion among all Spark Operators to appropriate a single Lightning payment would be fundamentally discouraged due to the small size of individual Lightning payments and the significant reputational ramifications associated with user theft, which would be readily detectable in light of inherent proof-of-payment structures in the Lightning network.

Privacy Considerations

It is crucial to understand that Spark, in its current configuration, should not be regarded as a privacy-enhancing tool, inheriting fundamental privacy challenges from Bitcoin’s foundational layer. While initial design choices may not adequately address privacy concerns, Spark’s core technology possesses the potential to achieve significant privacy enhancements with the introduction of blind signing for transactions, confidential amounts for token transfers, and additional privacy technologies not ordinarily feasible within the Bitcoin ecosystem.

Transaction Visibility

Transactions within Spark are not permanently published on-chain as in traditional Bitcoin transactions; however, all Spark Operators retain complete visibility into transaction activities. While theoretically offering some ephemeral privacy, the current practice involves transaction data being published on an explorer by Flashnet, a Spark Operator, allowing external observers to easily scrutinize Spark addresses and deduce transaction details, token balances, and potentially link Lightning payments to addresses through timing and amount analysis.

Efforts are underway to incorporate an opt-out feature for wallet developers regarding data publishing, allowing transactions to be marked as private. If successfully implemented, Spark Operators would commit to refraining from publicizing such transaction data while still having the ability to retain it locally.

Address Rotation Limitations

At present, Spark lacks support for utilizing multiple distinct addresses within a single transaction, a recognized limitation that developers are addressing. Consequently, this deficiency often results in implementations reliant on a single static address for transactions, rendering Spark’s privacy less effective than even that of on-chain Bitcoin. Coupled with visible transaction amounts, this makes it straightforward for an attacker to conduct timing and amount heuristics to ascertain the connection between Lightning payments and specific Spark addresses.

Spark Address Leaks

Furthermore, the core SDKs provided by Spark include the user’s Spark address in BOLT 11 Lightning invoices by default, unnecessarily exposing transactional data. This exposure permits individuals to decode a BOLT 11 invoice and access transaction histories associated with that Spark address, particularly due to the static address utilization and the publicly reported transactional data.

However, it’s worth noting that this characteristic can and should be disabled by wallet developers and is already remedied in Breez’s Nodeless SDK, which is gaining traction but remains relevant in this evaluation.

Further Reading

- Official documentation: https://docs.spark.money/home/welcome

- Bitcoin Layer 2: Statechains: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/technical/bitcoin-layer-2-statechains

Conclusion

Both Spark and Ark signify an exhilarating advancement in the realm of Bitcoin usability and scalability, albeit with their unique sets of trade-offs. While neither solution is without limitations, the existence of these competing and innovative frameworks allows wallet developers to integrate Lightning, native tokens, and other capabilities more seamlessly, alleviating much of the complexity traditionally tied to Lightning devices. Spark and Ark present a pragmatic pathway for scaling Bitcoin, aptly balancing user experience and trust-minimization.

As both protocols continue to evolve, there is optimism that the trade-offs associated with each will be addressed, resulting in improved solutions that enable broader access to non-custodial Bitcoin, thus enhancing the functionality extendable on the Bitcoin framework.

Gratitude is extended to the teams at Spark, Ark Labs, Second, Breez, Spiral, and Bitcoin QnA for their invaluable feedback on this article. Collaboration is essential to navigate the complexities of these novel systems, and the author is profoundly appreciative of the time contributed by each participant.

Thank you for visiting our site. You can get the latest Information and Editorials on our site regarding bitcoins.